The moment I arrived in San Francisco the city’s cool, moist air caressed the parched and splitting skin of my hands that had been desiccated by the desert air of Western Colorado and Arizona. Although it feels distinctly more edgy on the streets of SF compared with the last time I walked them 6 years ago the city almost instantaneously started to work its magic on me again.

It’s a huge cliché, but when I first came to SF in 1986 I was just another lost soul seeking inspiration and enlightenment. I quickly realized that the sidewalks weren’t paved with either of them, but after I returned several times to the City Lights bookstore, the Japanese garden in Golden Gate Park, then headed into the wine country of Monterey, Napa and Sonoma Counties all kinds of beautiful, dangerous and liberating ideas started popping into my head. However, during the last 6 years ago not only San Francisco but also Planet Wine changed dramatically.

“French winemakers used to look down on the California wine industry, but not any more. Now many Californian winemakers look down on places like Michigan and Virginia, Arizona and Colorado,” an anonymous American industry figure recently told me. My gut tells me that sentiment’s all prejudice, but for Arizona and Colorado I have fresh research, so I can back up that feeling with evidence and decisively say NO!

I just flew into SF after a few days in Grand Junction/Colorado for the VINco winemakers conference, then Phoenix for the 4th annual symposium of the Arizona Vignerons Alliance followed by 5 days traveling around the vineyards of Arizona’s mountainous North (pictured above is Caduceaus Cellars’ Judith Vineyard in Jerome) and the high plains in its South (pictured below is Rune’s new planting in Sonoita). The results of my research indicate that the term “emerging regions” for these places is not only patronizing, but also highly misleading, because there was significant wine production in both states prior to Prohibition. In the case of Arizona the history of winemaking goes back about around 400 years!

California certainly stole a march on those states during the late 20th Century, but that is not an adequate reason for some of the state’s winemakers, and all manner of other people across the US, to look down their noses at Arizona and Colorado and treat them as marginal areas with very limited potential for high quality wine production.

The spirit of California, also the spirit of Californian winemakers, was always one of daring to see and grasp new possibilities. It was freewheeling in the sense that there was not only a willingness to try the unfamiliar, but also to accept and live with the mistakes that would be made by choosing that path. I can’t tell you yet if California and the state’s wine industry still has that spirit, but the dynamic Arizona wine industry certainly has it.

It was my first trip to Arizona’s vineyards in almost five years and the leap forward both in quality and stylistic diversity was considerable. The red wines from producers like Doc Cabezas Wine Works, Caduceus Cellars, Callaghan Vineyards, Château Tumbleweed, Los Milics, Rune and Sand Reckoner Vineyards (in the latter case also the whites) now taste fresher, better balanced and more polished than almost anything that I tasted last time I was there. However, the most important change is the way they also taste way more striking than they were before. The best of them have strikingly original personalities that say, “I AM WHAT I AM and only this place, these people and this season could have made me that way!” This is the result of vision, a steep learning curve and the uncompromising determination of these winemakers.

Although Colorado is not yet as advanced with this process, there too I encountered a bunch of very well-crafted wines that had distinct personalities and would have no problem in the wine bars and restaurants of SF if they were given a chance. IF ONLY! The best of them were from Red Fox Cellars, Snowy Peaks Winery, Stone Cottage Cellars and The Storm Cellar. Here the range of grape varieties and blends is as eye-popping as in Arizona and must it too must be tasted to be believed.

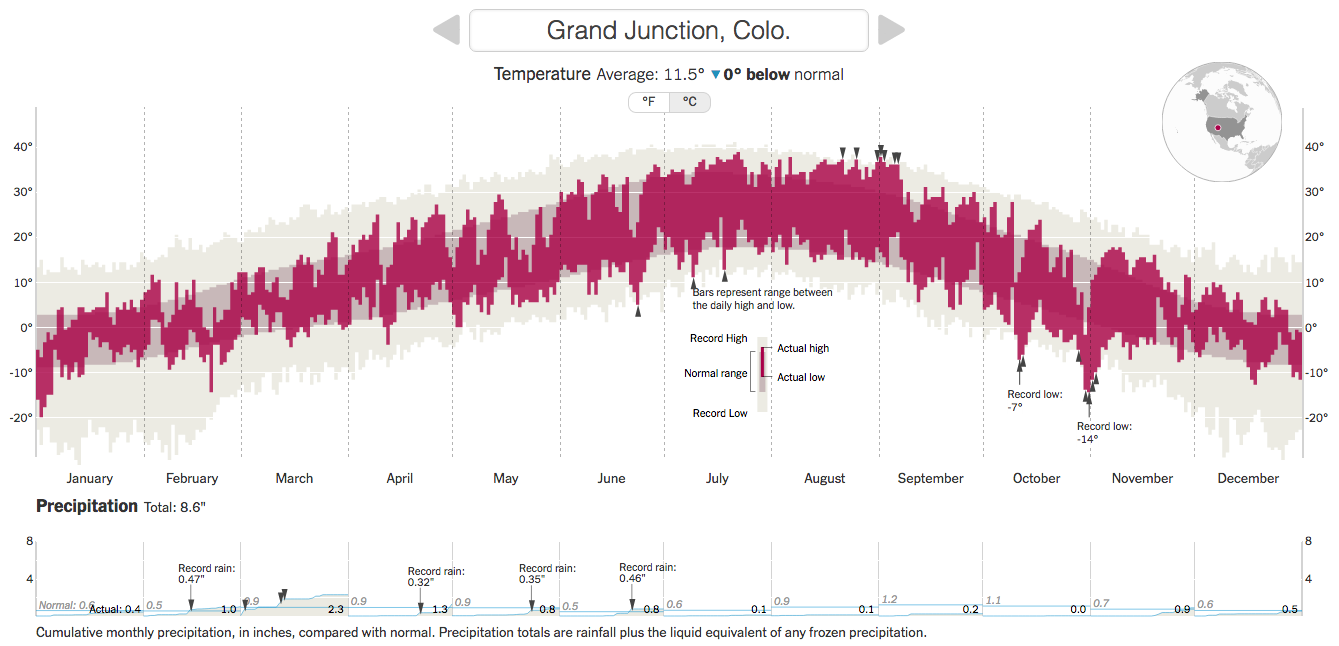

That might make it sound as if these two winemaking regions are cut from the same cloth, and it’s true that both are high-altitude wine regions with almost no vineyards planted below 1,000 meters/3,300 feet above sea level. However, climatically they’re very different. The biggest challenge in Arizona is the “monsoon” rains that descend upon the state’s vineyards shortly before the grapes are ready to be harvested and it is still warm, i.e. August/September. Of course, this can lead to rot, and sadly Riesling is one of the varieties that’s most susceptible to that. For Western Colorado the biggest problem is early frosts in fall, as happened in 2019. Just look at the graphic above (from an excellent interactive article in the New York Times about the weather pattern in 2019 around the world) that shows how Grand Junction experienced a sudden hard frost on October 10th. Not only did it make the curtain fall on grape ripening, but it also killed many of the vine buds for the 2020 crop and no doubt some vines of tender varieties too. Thankfully, the best producers saw this coming and picked their grapes of the late-ripening varieties (inc. Riesling) just in time.

Theoretically, California has a balmy climate compared to both these states. I remember how some Napa winemakers were shocked by the merest hint of frost back in January of last year. However, the fires of 2017 and 2019 in California wine country show that climate change has many ugly faces. Several farsighted producers in Napa now expect Cabernet Sauvignon – the region’s main grape with 65% of all vineyards and a grape crop value of $1 billion – to become untenable around 2030 because of the warming climate. Of course, they are preparing for that. Oh, and there’s a glut of unsold bulk wine. So, the reality is nobody has it easy and everyone is challenged. There is no Holy Land on Planet Wine!