HAUENSTEIN GROWING PAINS 4/5

My interview with Alexander van Dülmen in Effilee magazine #64

Nothing I’d experienced before was quite like my first couple of Hauenstein brainstorming sessions with Alexander van Dülmen at his townhouse in Berlin. Everything he said more or less precisely hit a nerve in me, so everything had to be noted down in some form. Even the least good ideas suggested other, better ideas. I marked the best ideas with a large exclamation mark and they were immediately incorporated into my scripts.

More important than any details of what Alexander said and how I noted it down was the way this process led to a heightened state of consciousness. Looking back from a distance it strikes me that this was the moment I overcame the shock of first seeing Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death (see 1/5). More than 35 years later I was finally responding actively to the painting , rather than recoiling in fear.

During the next phase of writing one by one the central characters gained clearer contours, becoming three-dimensional figures and friends I knew I would put through hell. That was essential, because when I approached Alexander had written about 90 minutes of material, but he saw Hauenstein as a 6 episode series with an episode length of 60 minutes.

It was clear to me that through the new energy the story had gained to would expand to fill 3 episodes without losing the pace of action. There would therefore have to be an entirely new story for episodes 4-6. This demanded that several secondary characters turn into central ones, and I added an entirely new central figure. The shadow of death fell very differently on each of those figures, so, I went with my new friends.

What I didn’t realize for quite some time was how my work was not in classic movie script form. Instead, my texts were an odd mix of theatrical plays and movie scripts. That might sound like a detail, but it was a problem, because it made them confusing for people in the film industry.

I also didn’t fully appreciate how extreme the four central characters and some of the secondary characters are. This is necessary in order to take the viewer to extreme places they would otherwise wouldn’t go. However, extreme characters tend to polarize.

In July 2023, I was confronted by all this when Alexander made an application for support for Hauenstein to one of Germany‘s regional film boards. It was an important learning process and it had a silver lining in what he wrote in the producer‘s note: just like in the mid-1990s , when Thomas Jahn who was working as a taxi driver and sent Til Schweiger the script for the movie Knocking on Heaven’s Door, so, at the beginning of that year I had sent him rudimentary scripts for the first episodes of Hauenstein.

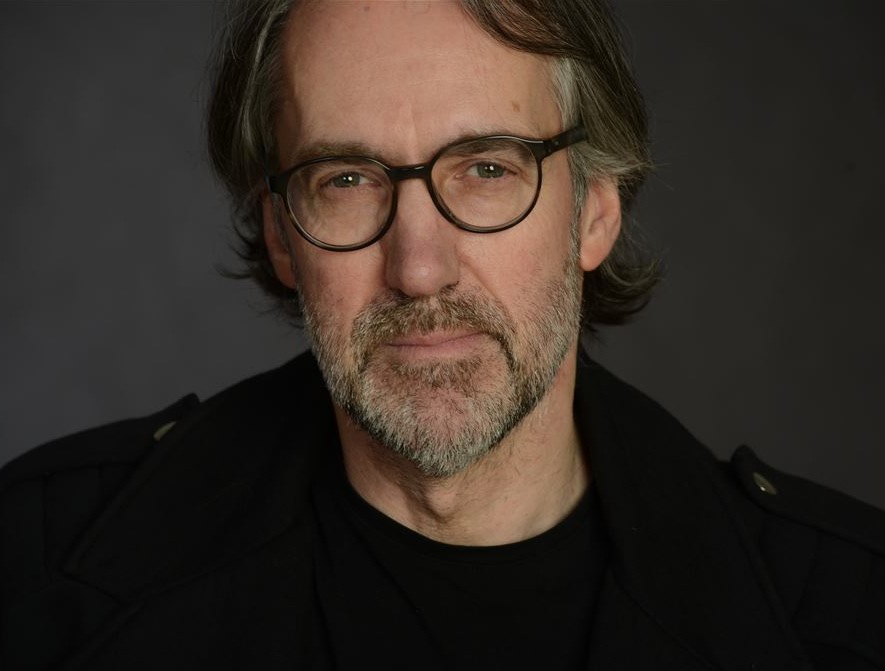

Jahn is now a successful director, so clearly, it is possible to make the leap into scriptwriting and filmmaking from outside the movie and TV bubble. It also confirmed that I was on the right track with Hauenstein, even though the film board felt that the scripts were not far developed enough to demand their support. More or less directly this lead to Alexander‘s decision that a director needed to be brought on board.

I first met Ziska Riemann at my small Berlin place in late October 2023, before we walked to Alexander ‘s townhouse for an initial brainstorming session. He also showed us one of the 11 „songs“ that make up his movie of the Peter Weis play The Investigation (Die Ermittlung in German), which was premiered in Berlin in July 2024. Watching this roughly 20 minute segment of the movie was harrowing.

The Investigation is about the first Auschwitz trial in Frankfurt/Germany in 1963-65. It is composed almost exclusively of the testimony of witnesses who were Holocaust survivors, and the responses of the accused. We all have images in our minds of the skeletal figures of the inmates and the piles of possessions stolen from the more than a million Jews murdered in Auschwitz by the Nazis. Of course, it’s not hard to see crude similarities between these images and Bruegel’s The Triumph of Death, but I think it’s essential to acknowledge the historical uniqueness of these terrible events.

Good as the connection between Alexander, Ziska and I was from that evening, the two nights we spent at Hotel Döllnsee in the Schorfheide heath north of Berlin at the end of January, 2024 were decisive. Ziska showed me how to reorder the scenes for the first episode of Hauenstein and add a couple of new ones that really focused the story. Later I would be surprised how easily I had sacrificed the first couple of scenes of the story I wrote in this process. She also pushed me into using a scriptwriting software called Drama Queen, now my main tool.

Several brainstorming sessions with Ziska at her home in Berlin followed. One day in the spring of 2024 I told her about how the Hauenstein story channeled my own feelings about death, and she encouraged me to intensify this aspect in the scripts . It was advice I followed, and this took the first episode to its present form.

At the end of May,2024 the three of us agreed that the decisive steps in the process of finding funding for the project should be taken during the following months. I continued work constructing the scripts for episodes 2 and 3, but both Alexander and Ziska were distracted by other projects. This was understandable, but slowly, over the following months it felt like the ground under my feet was turning to sand.

Finally in the spring of this 2025 we met up again and the trio snapped back into action.

Part 5 of this story will follow at a future date.