When I started writing my first version of the story of Hauenstein in Berlin 25 years ago filmmaker Thomas Struck was delighted by the way I was fascinated by the character he had created many years previously. And for a moment it seemed that we might successfully cooperate on the realization of a Hauenstein movie.

After a long brainstorming session at the dining table of my Berlin home on the 30th December 2000 Thomas wrote a note that told Hauenstein’s life story. It was full of humour and playful eccentricity. Hauenstein was an artist and it was drawing that magically kept him alive beyond three score years and ten. Of course, that made Hauenstein a wonderful fairytale figure. I saw it very differently, feeling that the story had to have some hard edges, so I rather quickly realized that cooperating with Thomas wasn’t going to work.

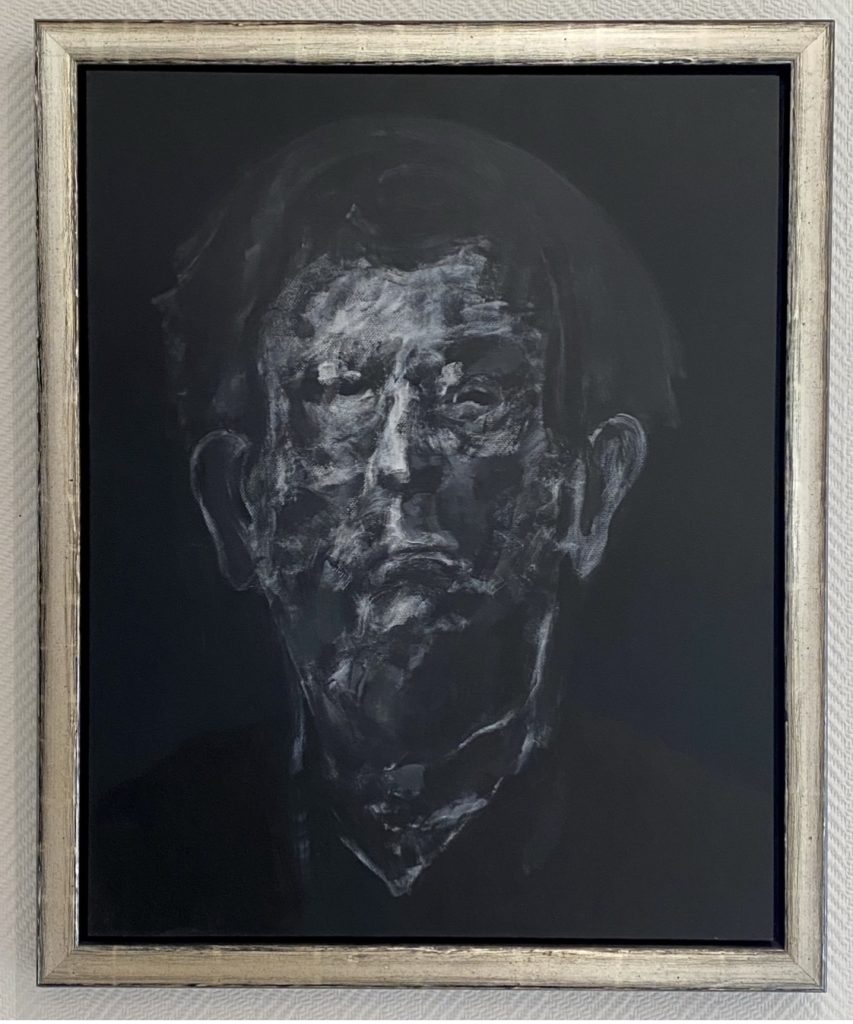

During the spring and summer of 2001 I plowed ahead alone, writing a number of texts, including quite a lengthy fragment of a movie scrip . However, I had no experience of scriptwriting, and the story woefully lacked real tension. More fundamentally, I didn’t sense the deep connection was between Hauenstein and the tight knot of emotions that Peter Breugel’s The Triumph of Death (1562) had unleashed when I first saw it in 1984-5. My involvement with Hauenstein was, and is, a reverberation of that moment. This is how I saw him in 2001 as documented by a painting I did that year.

Not only do audiences live vicariously through the characters in movies, but filmmakers and scriptwriters do too. Hauenstein was the focal point where my rational awareness of the inevitability of my own death and the irrational desire to overcome it collided like sub-atomic particles in an accelerator, releasing enormous energy. I should have sought strength and inspiration there, but I only vaguely sensed its presence inside me. At the same time many weak ideas led me astray and confused me.

In September 2001 I started writing a regular column in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung’s (Germany’s equivalent of New York Times) new Sunday edition, and not long after a wine book project was accepted by an important German publisher. I jumped at these things and let Hauenstein drift off.

For many years from after that writing about wine felt right. This distracted me from my psychological problems and my failing marriage. Although I wrote a string of German language books and some of them sold quite well, none of them was published in my mother tongue. I was heading deep into an artistic dead end.

Co-writing and presenting three series of TV documentaries about wine for Bavarian TV (BR) from 2010 to 2012 reconnected me with filmmaking. I learned a lot from everyone in the team, most of all from the director Alexander Saran. This project also kept me psychologically on a halfway even keel through those troubled years. By the time I admitted to myself that I was lost and sought the help of a therapist I was suffering seriously from depression.

When I left Berlin for New York City at the end of November 2012 my plan was to finally write an English language wine book and to shoot my own movie, an autobiographical mockumentary called Watch your Back. The book appeared under the title Best White Wine on Earth in June 2014 (published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang), and around the same time there were several screenings of my low budget 65 minute movie.

However, that was the superficial action of this period. Of far greater long-term, importance for me was reading Story by Robert McKee, the man who can fairly be called the guru of screenwriting. That process stretched over the four years of my sojourn in NYC lasted (with numerous trips back to Berlin, where I always had a room). I am still rereading that book today, just like Elias Canetti’s Crowds and Power (see episode 1).

When I started reading Story it brought me to a humbling realization: the great majority of what I had written so far was deeply flawed. What to do? Obviously I wanted to write better stories and I realized film might be a more interesting medium than books. However, the next steps turned out to be much more difficult than I hoped and expected. The general crisis in journalism caused by the expansion of the social media suddenly caught up with me big time after the publication of Best White Wine on Earth.

Another job like working as a wine taster and editor for JamesSuckling.com wasn’t going to come along, so in August 2016 I grasped both it and financial security. I’m still doing that job, but I lost my foothold in NYC at the beginning of November 2016. Marrying again in Germany helped me over the sense of loss for my NYC.

As I approached my 60th birthday the Covid crisis hit and the death toll in NY was 25 times that of the German average! Perhaps it was the new landscape of death in intensive care units and refrigerated containers used as morgues that prompted me to pick up Hauenstein again? A journalist friend in NYC called Jürgen Fränznick had sent me some of those horrific images.

Another journalistic colleague Paula Redes Sidore in Germany read my first hesitant sketches for a new version of Hauenstein in September 2020 and encouraged me to pursue the project. My old Berlin friend Caroline Stummel helped me dig out many of the old Hauenstein papers, which lay in various dark corners in the city. Then, TV and film scriptwriter Thomas Wendrich provided useful criticism of the first draft of my script in June 2021, but would anyone in the film industry be interested in a self-taught scriptwriter with a story that didn’t fit neatly into any established genre?

In April 2022 I had dinner with a couple of friends in Berlin and told them about the script I was working on. Nadine Rosinski, who also works in wine, told me she had a good contact to the film and TV producer Alexander van Dülmen who also was a wine merchant. She kept her promise to speak to him and contact with him was established.

It’s only a short bicycle ride from my Berlin pied á Terre to the home of Alexander van Dülmen. We first met there in June 2022 and two months later I did an extensive interview with the film producer-wine merchant extraordinaire for the German-language Effilee Magazine. After the interview we went into the garden of his townhouse, he told me he had read my script and was interested.