This is the second installment of the talk I gave at the Riesling Fellowship evening in the Vintners Hall in London on January 29th. To fully grasp the context of the below it would help to read my previous posting (Part 1) before this one. Philip Eyres (1926 – 2012) was not only a great wine merchant, he was also a man with a strong sense of justice and great compassion. I spoke about these things the last time I saw him, and I promised him that I wouldn’t let the subject of this talk drop. Whether the Vintners Hall was the right place to say these things is debatable It seemed to be so to me, because it is the home of the Establishment of the British wine trade.

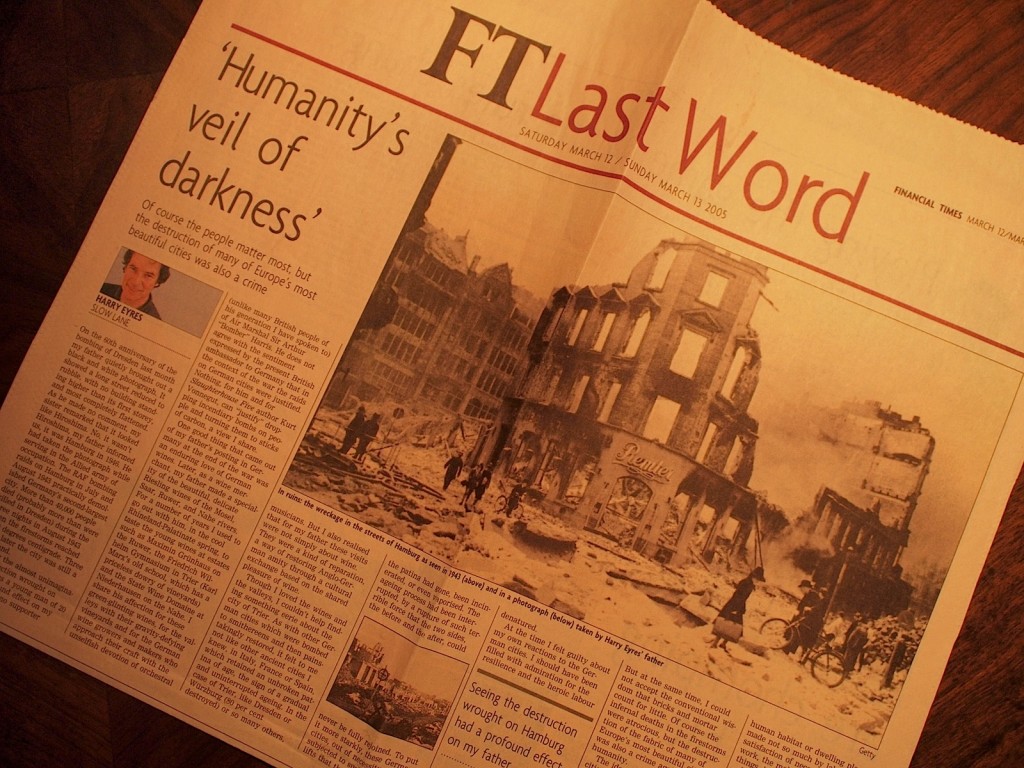

Then something Philip Eyres did 10 years ago changed everything. Harry Eyres describes this so well in his Slow Lane column in the (London) Financial Times of March 12th/13th 2005 (pictured above) that I will read the first half of his column (I pick up newspaper clipping and begin to read).

HUMANITY’S VEIL OF DARKNESS

On the 60th anniversary of the bombing of Dresden last month my father quietly brought out a black and white photograph. It showed a long street reduced to rubble, with no building standing higher than the first story, and most completely flattened. As he made no comment, my sister remarked that it looked like Hiroshima. No, it wasn’t Hiroshima, my father informed us, it was Hamburg in 1946. He had taken the photograph while serving in the Allied army of occupation. The RAF bombing raids on Hamburg in July 1943 practically demolished Germany’s second-largest city. More than 40,000 people died (probably more than were killed in Dresden) during the three nights in July 1943 when the firestorms reached 1,000 degrees centigrade. Three years later the city was still a wasteland.

Seeing the almost unimaginable destruction wrought on Hamburg as a young man of 20 had a profound effect upon my father. He is no supporter (unlike many British people of his generation I have spoken to) of Air Marshall Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris. He does not agree with the sentiment expressed by the present British ambassador to Germany that in the context of the war the raids on German cities were justified. Nothing, for him and for Slaughterhouse Five author Kurt Vonnegut, can “justify” dropping incendiary bombs on people and turning them to sticks of carbon, a view I share.

One good thing that came out of my father’s posting in Germany at the end of the war was an enduring love of German wines. Later, as a wine merchant, my father made a specialty of the beautiful, delicate Riesling wines of the Mosel, Saar, Ruwer, and Nahe rivers. For a number of years I used to go out with him, in the cool Rhineland-Palatinate spring, to taste the young wines at estates such as Maximin Grünhaus on the Ruwer, the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium in Trier (Karl Marx’s old school, which has a priceless dowry of vineyards) and the State Wine Domain at Niedershausen on the Nahe. I share his affection for these green-glinting wines, for the valleys with their gravity-defying vineyards and for the German wine growers and makes who approach their craft with the unselfish devotion of orchestral musicians. But I also realized that for my father were not simply about wine. They were a kind of reparation, a way of restoring Anglo-German amity through a cultural exchange based on the shared pleasure of wine.

Suddenly, I realized that for 20 years I had unknowingly been involved in Philip Eyres personal campaign of reconciliation, and his work of reparation. I was immediately reminded of a conversation with a German wine journalist colleague, Pit Falkenstein, back in the summer of 1998. I had already known Pit for some years, but knew little about his life. On a walk through the vineyards of Assmannshausen in the Rheingau he told me his life story. (I put down newspaper clipping and pick up an email). Pit was born in Berlin in 1935. After the family home bas bombed out during the war they moved to a safe place, the Salzkammergut area of the Austrian Alps. Pit was sent to Stift Admont, a monastic boarding school. At Easter 1945 the food ran out and the monks sent the younger children home. Here is the story in his words:

There were many groups of four or five boys. A 13 year old lead our group…The trains were not running any more. I therefore marched the 60 kilometers to the Salzkammergut with my group in two and a half days. The two sandwiches each we were given at Admont were quickly eaten, because we were hungry. We slept in barns on hay and friendly farmers gave us plenty to eat. On the second day as we had almost made it to Tauplitz we were surprised in open fields by Spitfires. We were making our way up a hillside meadow between large rocks. We tried to reach the nearest piece of woodland, but didn’t make it. The British pilots shot mercilessly at us with their machineguns. We lay flat on the ground and were very lucky. Almost nothing happened to us. One friend of mine was grazed by a bullet on his right shoulder. The heel of my right shoe was blown off. Only some minutes later did I realize that my left hand was bleeding. A tiny piece of shrapnel from a bullet that had hit one of the rocks next to me and flown into my middle finger. To this day I carry this “trophy” around with me.

Stuart, why did those pilots do that?

I was very shocked by that story when Pit Falkenstein told it to me, but I also felt terribly confused. What did it have to do with me? I was born in 1960 and my parents were children during the Second World War. Only much later did I realize that my maternal grandfather had been an electrician in the RAF and worked on fighter planes. Quite possibly, he had serviced the planes that shot at Pit Falkenstein and his school chums.

TO BE CONTINUED VERY SOON!

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12009.jpg)

Pingback: Berlin Riesling - Bloggiges