By Paula Sidore & Stuart Pigott

Here is the first half of the presentation that Paula Sidore (pictured above) and I made at the ProWein 2020: ProWein International Media Summit at the Geisenheim Wine University in the Rheingau/Germany on the 21st November 2019. The second half – coming soon! – includes what we said about the 6 wines we poured that day. Minimal editing was been undertaken for the sake of clarity.

Paula Sidore: I am an American wine writer, certified sommeliere and translator, specializing in German wine. I came to Germany from the USA in 2002, shortly before the summer that really seemed to “kick off” the awareness of Climate Change here in Europe, here in the wine industry. It was the point at which people – my president perhaps excluded – could no longer deny what was happening. 2003 presented conditions unlike anything many producers – especially those in traditional cool climate regions – had ever seen before. People died; crops withered. This was the point at which winemakers realized that talking, noticing, watching wasn’t enough. This was the point at which they knew: “We have to do something different.”

Now we’ve all spent the last 24 hours learning about the threats of Climate Change to an industry we hold near and dear to our hearts, our pens, and our lips. And even if this information we’ve been receiving is upsetting, overwhelming, and frankly depressing, Stuart and I are here to present you various approaches to sustainability, or, as I like survival.

Our presentation is called: Stayin’ Alive — we decided to spare you the sound track but imagine it running in the background. Since 2003 we’ve all been talking about Climate Change, but I’d like to change the vocabulary. See for me a Change implies a start and an end. It’s finite. If the last 15 years have done anything, they have proven to us that what is happening is anything but finite. It’s ongoing and its unpredictable, a locomotive barreling down on us with no indications of stopping. And farmers, winegrowers included, are in the crosshairs, standing on those railway tracks. So, for me, I prefer to think of it as a Challenge. A Climate Challenge. We all need to figure out an approach, realistically many varied and ever changing approaches to survival.

And part of that survival is based on resilience, on figuring out how to preserve a centuries’ long history and tradition, in many cases taste, in a changing world. Ripeness levels are rising, and with them alcohol levels. The last really “cool” vintage we had here in Germany was likely 2010, and in Bordeaux you have to look even further back than that to 2002.

And yet the modern palate is crying out for Freshness! Lower Alcohol! More Acid! LIght, bright, lean and green. According to the PW Business report, 63% of retailers expect consumers to demand lighter and more refreshing wines as the shift in seasons continue. Even as longer, hotter summers continue to naturally bring heavier, riper and hotter wines. A very real and very difficult dilemma, because there’s no silver bullet for it. Perhaps it’s simply a case of people want what they can’t have, but I don’t think so. And regardless, part of survival is not just getting the wine produced, but also getting it sold. So what’s a winemaker to do?

There are as many survival options as there are wine regions. And over the course of an hour we certainly cannot even begin to cover them all. I do think, however, that it’s possible to break them down into 3 basic categories.

I Change the LOCATION in the polar and/or high altitude directio

1.10% of producers for the ProWein business report 2019 reported moving to different vineyards, with 17% considering such a move in the near future.

2. Grapevines have long thrived best in borderline environments and today Winemakers are pushing those limits: by seeking out cooler climates

3. Poland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway (2018 saw a Norwegian Riesling from Klaus Peter and Julia Keller of 76°Oechsle at 58° North!)

II Change the set up of the VINEYARDS: 60% of producers reported specific adaptations taken or planned in viticulture as a result

1.Growers are looking to curtail sunlight exposure of the grapes and/or canopy through a number of approaches in order to prevent overripening, rather than prevent under-ripening as had been for years the thinking

2. Change in exposition, vine height, canopy, variety and rootstocks that might do better in riskier conditions (frost, drought, etc)

3. 14% of wine producers in the ProWein business reported already having experiencing the need for other grape varieties due to climate change. 24% are planning change of this kind

Here New World winemaking has an advantage, as they are not legally restricted as the Europe is in terms of varieties and winemaking methods. This gives them the freedom to pursue a number of different approaches in a short amount of time to see what works best

Boredeaux is allowing seven additional non-traditional grape varieties into the appellations Bordeaux and Bordeaux Superieur to mitigate the effects of climate change on the region

III Change the CELLAR (inkl. packaging)

1.Whole cluster pressing, yeast selection, blends, reserve wines under pressure, etc

2. One in two large wineries and bottlers reported having to employ new enological technologies to adapt their wines to market needs

3. Packaging: lighter glass bottles, since glass production is energy intensive:

For example, according to Jackson Family Wines who have been measuring their greenhouse emissions since 2008, they found that glass bottles from production to delivery accounted for 25% of the company’s greenhouse-gas emissions. Moving to lighter bottles immediately reduced their emissions by 3%.

Stuart Pigott: What does sustainable really mean? Mostly, for the contemporary wine industry it means certification that the producer/importer/distributor/retailer/restaurant/bar can hold up to show they are on the right side of the moral divide. In many places around Planet Wine consumers percepeive a moral hierarchy of these certifications with producers who are “natural” and biodynamic right at the top, then, in descending order, those who are biodynamic or natural, organic producers, sustainable producers and, at the bottom of the ladder, small conventional producers followed in last place by those of an industrial scale. I don’t want to knock sustainable certification of any kind, and I am certainly not attempting to make any moral judgments myself, but for me sustainability is all about survival. Given the Climate Crisis we find ourselves in due to the acceleration of global warming, that‘s the real S-word on Planet Wine in the 21st century.

Of course, survival has multiple meanings. What’s the real bottom line? I suggest it’s the question if we have enough food to eat and water to drink, a matter we will have to think about during the coming decades, even in the wealthiest countries as crop shortfalls due to climate change become more common and severe. However, on Planet Wine whether we can still get, or will still be able to get, the styles of wine and wines from the grape varieties we want is also a question of survival. I’m going to call it cultural survival – the survival of things we don’t want to lose, like the Wehlener Sonnenuhr vineyard on the Mosel (pictured above) and the Riesling vines planted there. That example makes it clear that cultural survival also has social and economic aspects.

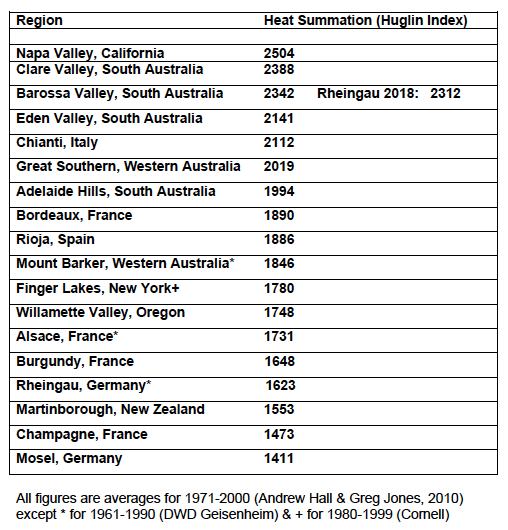

To show you where we really are now and why climate change really raises the issue of survival I have a couple of charts to show you. The first of them (below) shows the heat summations on the Huglin Index for the vine growing season (April – October in the Northern Hemisphere, the opposite end of the year in the Southern Hemisphere) for a range of winegrowing regions during the latter part of the 20th century. Today, we are in Geisenheim in the Rheingau, so I suggest that you look at the bottom end of the table to see where this region was a generation ago.

You need to look up the table a long way to find where it would stand, because 2018 was the warmest year ever recorded in Germany, that is, since Geisenheim started regularly collecting weather data in 1884. With 2312 on the Huglin Index it was almost as warm in Geisenheim as on the floor of Barossa Valley, and that’s a region mostly associated with powerful Shiraz (Syrah) reds with alcoholic contents of 14% – 15% plus! In 2008-9 I was a visiting student at the Geisenheim Wine University and back then I learned this is where the climate models said we would be around 2050! That and the heat waves of late June and July 2019 are the reasons that earlier this year I wrote the headline Cool Climate is Dead in Old Wine Europe.

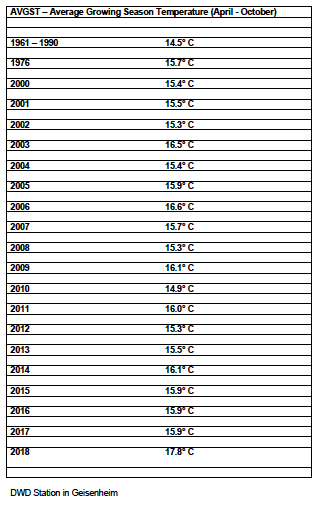

The second table (below) gives an overview over what happened in recent years. Each vintage is the product of the weather during the growing season and temperature is the most fundamental aspect of that. During the period 1961-1990 the average temperature during the growing season in Geisenheim was 14.5°C. Then the majority or vintages had average temperatures in the 14.0° – 14.9°C range and gave more or less good wines, but several times per decade there were poor vintages with average temperatures below 14°C and then there were problems with un-ripeness, meaning green aromas, aggressive acidity and gritty tannins.

The top vintages were those with those years with average temperatures during the growing season of 15°C or more. A lot has been talked about the fact that Riesling is a cool climate grape variety, but actually it was only in those vintages that it came close to optimum ripeness, e.g. 1971 & 1976 in the 1970s when the harvest was also significantly earlier than in those vintages with average temperatures below 15°C. Of course, this raises the question as whether the characterization of Riesling a cool climate, late-ripening grape variety is entirely correct. At least to some degree it is a legacy of the conditions that were typical during the last centuries. During the Middle Ages Warm Period conditions were more like those today than the situation in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Of course, the 2018 vintage raises the question whether it is now, or will soon be too warm for Riesling in Germany. Certainly, the fact that the last poor vintage, i.e. growing season with an average temperature below 14°C, was 1984 and that’s a long time ago. Just look at what happened since 2000, there was only one vintage, 2010, with an average temperature below 15°C (the previous ones were 1996 and 1991)!

If we turn back to Table 1, then close to the top is Clare Valley in South Australia. The largest Riesling growing region in the Southern Hemisphere has a higher heat summation than the floor of Barossa Valley, but the Riesling grape still gives crisp and aromatic wines there! This has a lot to do with not the dramatic diurnal temperature shift there; something Clare has in common with many other New World Riesling regions such as the Columbia Valley of Washington State/USA and Marlborough at the northern tip of the South Island of New Zealand.

Clearly, Riesling has a wider climatic range than is commonly supposed by most people in the wine business (never mind consumers), but as Professor Schulz of the Geisenheim Wine University, one of the problems we face in trying to plan the vineyards of the future is that we don’t know what the upper warmth limit is for many grape varieties. Wine growing regions at the cooler end of the climate scale for winegrowing where climate change has been more pronounced have entered uncharted waters.

Watch this space for Part 2!

Excellent article … observation… a topic that is be becoming more and more acute in Virginia and elsewhere. Cheers for good climate🤔🍷