“Those who deny history are condemned to repeat it,” George Santanaya

This is the fourth and final installment of the talk on my Life and Riesling I gave at the Riesling Fellowship evening on Thursday, January 29th at Vintners Hall in the City of London. My apologies that a mere 15 minutes had to be broken up into four chunks, but I was anxious not to overwhelm readers with too much uncomfortable truth in one go. I think this is all much more difficult to take when read on the computer screen than when spoken. Some will say that by publicizing this I have done myself a disservice, but I owe a debt to wine merchant Philip Eyres (1926 – 2012) and continue pursuing what we discussed and corresponded about at the end of his life. It was he who helped me onto the Riesling trail that I’ve followed for more than 30 years.

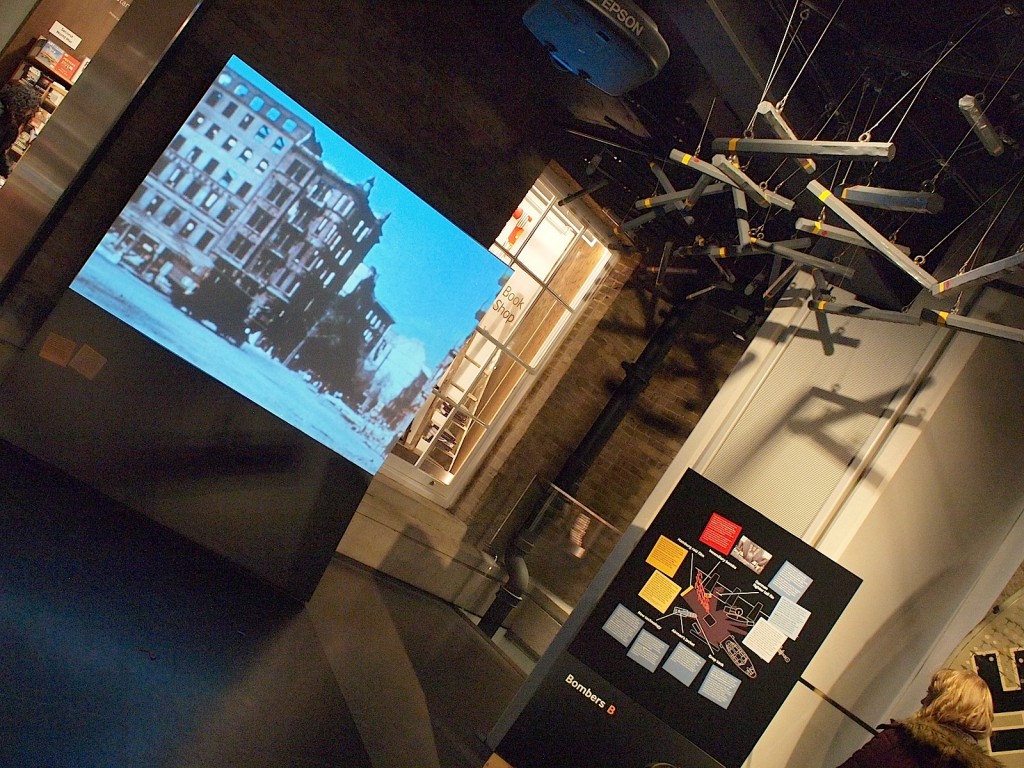

I have to start by reading you a short section of Philip Eyres’ letter to me of 16th January 2012, written just a few months before his death: “On the subject of bombing during the last war, I always felt moral repulsion of the way that civilians in Japan and Germany were targeted and the fact that this was largely concealed from public knowledge… While “Bomber” Harris is generally assumed to be the architect of the attempt to win the war by killing civilians, Churchill must take the blame.”

This is an unpopular view even 50 years after the death of Winston Churchill. He is now the central figure in the mythical WWII in British minds and hearts, at once super-human and super-British, his weaknesses (for example, his well-documented white supremacism) are still rarely discussed, and then usually only superficially. The reason for this is the key part that he plays in the mythical WWII, the purpose of which is to create a patriotic sense of national identity. That’s another subject though, that this blog posting can only touch upon. Let me give you a few quotes from Winston Churchill from 1940-41 that show how early he had set his mind upon the so-called “Area Bombing” (i.e. carpet bombing of residential urban areas) campaign against German civilian targets that began in 1942 and reach its climax during the spring of 1945.

“We will make Germany a desert, yes a desert!”

On the subject of Adolf Hitler: “But there is one thing that will bring him back, and bring him down, and that is an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers from this country upon the Nazi homeland.”

“There are less than 70 million malignant Huns, some of who are curable and others are killable.”

It is perhaps important to point out that it was clear to all the leading members of the British government and the Royal Air Force that the policy of bombing German civilians targets during WWII was in contravention of international law, specifically the 1907 Hague Convention to which Britain was a signatory. It explicitly banned all attacks from the air on civilian population centers far from front lines. Of course, there is the argument that the Nazi atrocities, particularly the obscenity of the Holocaust, were so terrible that anything was acceptable in the struggle against them. I obviously don’t agree with that, for the simple reason, because it is based on the idea that a great wrong on one side justifies a smaller one on the other side, that an orgy of killing demands more killing a revenge for it.

Philip Eyres was very struck by the following quote from the physicist Freeman Dyson (born 1923). In it he describes his work in the office of Air Marshall Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris during the last years of WWII: I sat in my office until the end, carefully calculating how to murder most economically another 100,000 people. Dyson then turns to the organizers of the Holocaust and observes, They sat in their offices, writing memoranda and calculating how to murder people efficiently, just like me. The main difference was that they were sent to jail or hanged as war criminals, while I went free.

Today, the assumption is often made that WWII was fought by the Allies against the organizers of the Holocaust with the aim of stopping them. While it is true that when the Allies found out about the extermination of the Jews the British and American governments made statements in parliament and congress condemning this, they didn’t follow through after that. Those statements were made in December 1942, but not only did no significant action follow those fine words, no serious attempt was made to determine what action could have been necessary to obstruct the Holocaust. Instead, the Allied leadership stood by while the Jews were exterminated by the German Nazis and like-minded citizens belonging to many of the nations Germany had occupied.

What was the attitude of the British government to the fate of the Jews? In early 1943 the Bulgarian government requested that Britain allow part of its Jewish population to be transported to Palestine. Britain refused. Shortly after this the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden wrote in a memorandum: There is a possibility that the Germans or their satellites may change over the policy of extermination to one of extrusion, and aim as they did before the war at embarrassing other countries by flooding them with alien immigrants. For extrusion read deportation, and for alien immigrants read Jews. The Bulgarian Jews, though sadly not those in Bulgarian occupied Thrace and Macedonia, were lucky to be saved by their government’s repeated refusal to follow the German instructions to deport them to the death camps in what is now Poland.

My training as a cultural historian (Royal College of Art, 1984-86) taught me that the most fundamental question concerning history is what we choose to remember and what we choose to forget. Systematic forgetting is a form of active denial, and it is possible to be in denial for a very long time. Keeping the great majority of the population in ignorance is a very effective method of preventing them breaking such a cycle of denial. Philip Eyres and I came to the conclusion that the British establishment has been very good at denying chunks of the nation’s history, of which the bombing of Germany civilians during WWII is a prominent example. The problem is that, as the Spanish philosopher George Santanaya (1863 – 1952) famously wrote, those who deny history are condemned to repeat it.

I’m pretty sure that today RAF Tornados took off from air bases in Cyprus to bomb targets in Iraq. It is a little-known fact that the first RAF raids against targets in Iraq were in 1922 as part of a policy called “air policing”. The attack on Samawah in Iraq of November 30th/December 1st 1923 left the town in ruins with an unknown death toll. This happened 14 years before the destruction of Guernica by the German Lufwaffe during the Spanish Civil War. The architect of the “air policing” policy was Winston Churchill during his short period as Colonial Secretary 1921-22. A certain Arthur Harris was one of the RAF squadron leaders in Iraq.

It was Philip Eyres and German Riesling that lead me to these painful conclusions.

POSTSCRIPT

How did I succeed in upsetting some of my countrymen with the above words?

In ‚A Room of One’s Own’ Virginia Woolf (1928) talks about how male self-confidence and self-assurance are generated through “looking-glass” games involving women who accept looking smaller than the men they “reflect” in order that the latter feel bigger, more important. Of course, the smallness of women in such games is no less illusory than the size of the men which they serve to magnify.

Racism and nationalism do much the same. By thinking down and talking down the natives of a distant land or the inhabitants of a nearby country the members of the dominant group build themselves up in their own minds. There’s no reason why such games can’t be played retrospectively.

I think that the myth of Britain’s absolute moral victory over Germany in WWII that many of my countrymen frequently replay is just such a retrospective game. Like the sexist looking-glass game it too depends upon selective cognition, in this case the quiet ignorance or the forceful denial of historical facts.

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12001.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12009.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12008.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12007.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12006.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12005.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12004.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12003.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12002.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x12001.jpg)

![120114_riesling_global_RZ [1600x1200]](http://www.stuartpigott.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/120114_riesling_global_RZ-1600x1200.jpg)